I’m a huge fan of the Pauling hypothesis (or more correctly, one of the Pauling hypotheses, some which are crap). To remind you, Linus Pauling was the Nobel Prize winning scientist who is one of the founders of the field of molecular biology. He started the Vitamin C craze. This particular theory of his (again, compared to some of the others) is pretty much rock solid, and explains both his enthusiasm *and* why skepticism is so high:

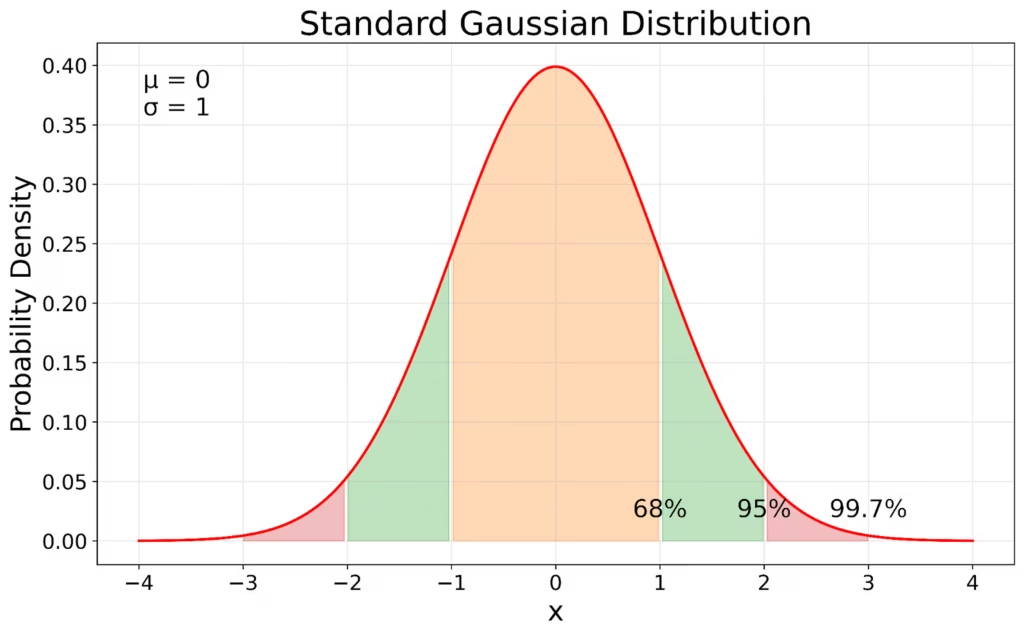

1) Assume that you have a distribution of requirements for a vitamin, say vitamin C. While the distribution is likely not a Gaussian, we’ll use one for argument sake:

(graphic taken from here)

So, now consider how the RDA (recommended daily allowance) of a vitamin is computed. First an estimate is made of this distribution, with the “Estimated Average Requirement” (EAR) calculated as the amount that meets the needs of 50% of the population. The RDA is set at two standard deviations above the EAR.

As we all know, 2 SDs around the mean cover 95% of people assuming (again incorrectly) a non-skewed gaussian distribution. Since the minimum requirement covers the 2.5% at the lower end, that means that basically the RDA is sufficient for 97.5% of the population. That is definitionally the goal.

2) 97.5% of the population, is pretty good. For many folk, particularly in well-fed America, the average diet provides that and more. Of course it doesn’t always cover 97.5%, because the distributions are sometimes not really gaussian, and some are likely skewed to the right, but again, it’s good enough for government work. But…

3) Here’s where the difference between aggregate statistics and individual needs arises. It’s one thing to say that the RDA covers 97.5% of the people. It’s essentially impossible to determine before supplementation whether an *individual* patient is in the 97.5% cohort or the 2.5% cohort.

There are, of course, lots of reasons to be overtly vitamin deficient — we all know the issues with vitamin D in the elderly, B12 and folic acid deficiencies in various groups, B1 in alcoholics, etc. But…. again…. what about those folk who simply utilize these things inefficiently? They will have a “normal” level of vitamin, but *still* be deficient. Or, who, because of their gut microbiome or other reason simply don’t absorb it so well? They will eat enough, but not get it into their system.

Because of these groups, and some in the other groups, if you pick a person out of the crowd and ask “Is this person in the 97.5% or the 2.5%” the answer is that you don’t know, and there’s no way of knowing unless they show overt symptoms or improve with therapy. Unfortunately, low grade deficiency often provides little or very nonspecific problems that only are manifest by increased risk for various diseases that are not clearly vitamin-related (e.g. immune dysregulation).

4) This is particularly a problem with the fact that there are multiple vitamin and micronutrient requirements. Let’s say that there is a 2.5% chance that the RDA is insufficient for a given person. If one (again incorrectly) applies aggregate statistics to individual then that implies the probability that he or she is fine is 97.5%. But now add another vitamin. Assuming independence, the probability that he or she is fine regarding both is .975 squared, or 94%. Now lets look at 20 vitamins, that’s .975^20, or 60% likely that this person is doing in fine for all 20. For 30 micronutrients, it’s 47%.

Why isn’t everybody sick? Because most people get way more than the RDA, so they are already “overdosing” on their micronutrients. So, most folk with higher than normal requirements are meeting those higher than normal requirements. Unless they eat poorly.

But that pushes the problem of whether or not a particular individual is in the 2.5% cohort into a problem of whether that person is in, say, a 1% cohort. It moves the goalpost, but doesn’t change the problem. How do you know if *you* are a person with a higher than normal requirement that isn’t met with your daily dose of Big Macs and fries?

You don’t.

5) So.. here’s what Pauling said to do. You can’t take megadoses of everything, of course, and some things are toxic at high doses. So, find those micronutrients that:

a) Are safe at extraordinarily high doses, and

b) Cheap

Take high doses of that. If it helps you, you’ve won the lottery. If it doesn’t, you’ve wasted a few cents. This is why Linus Pauling advocated taking vitamin C — because that is the perfect example of that. If you take a boatload of vitamin C, it won’t hurt you. It’s cheap as dirt, so if it doesn’t help, you’ve wasted a few cents a day.

Will it help you? Will it keep you from getting a cold or cancer or whatever? Probably not. Unless you are in that 1% cohort. Then it will. The kicker is that almost no prospective study will find that 1% cohort, so those studies will *always* show no benefit — it’s a design feature of aggregate statistics almost no study will have that much statistical power. One percent cohorts don’t usually count unless you know to tease them out beforehand.

But now let’s go back to that multivitamin study, and the problem of joint probabilities. If I do a study on vitamin C, because only 1% – 2.5% of people will respond, it will *never* have the statistical power to find them. But, let’s go back to that issue of 30 vitamins. If you look at multiple vitamins simultaneously, that means you should find a result in (1-.99^30) to (1-.975^30) or 26% to 53% of folk. Of course, it won’t be that high, because you don’t really know what outcomes you really need to look at, and the outcome improvements will be varied, usually minor in the short to intermediate term, and often subjective (e.g. energy level). Only a small proportion of people who benefit will benefit in terms of long term cognitive decline, for instance. So, if you look at only one outcome, the result will be small.

Thus, for instance, if you look at high dose B vitamin supplementation and atherosclerosis (not megadoses of niacin, but just extra B complex), you find a lot of positive effects that are not statistically significant — exactly what you’d expect from large studies that have small cohorts that benefit. Or, you get mixed studies, with some showing benefit and some not (e.g. high dose B vitamins and stroke risk). However, if you look at high dose B complex supplementation and more generalized measures such as subjective “well-being” and “response to stress” (which covers a wide variety of sins), the results are significant in aggregate — because it’s an indirect aggregate measure of multiple cohorts.

A perfect example of that, by the way, is my wife and her response to Armour thyroid. Armour thyroid has no increased benefit in patients, unless you tease out a specific cohort and measure things like subjective “well-being.” Then, it’s great, but only in that one cohort. Otherwise, it’s a waste.

So, should people take multivitamins? Only if they are very cheap. Will they benefit? Only if they are in specific cohorts. You just don’t know if any individual is in that cohort — and there’s no large study that can tell you.

In my own case, I can tell you my story, and why I am so hot on this. Back when I was in the military and at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology in DC in the 1990s, I was a physical wreck — even though I was in the best ‘shape” I’ve been in my life. I was at optimal weight, ran every day, lifted weights, etc. But i felt like crap. I had three to four painful episodes of nephrolithiasis per year. I had recurrent rosacea. I had horrible hidradenitis suppurativa (a disease I would not wish on my worst enemy). I had recurrent pneumonias, with slowly declining respiratory function as the years went on. Then I read an article somewhere about rosacea and vitamin supplementation (for a more recent review, see: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00403-024-02895-4 ). So, I started taking high dose B vitamins. Over the next three or four months, my rosacea disappeared, I stopped getting stones, and I stopped getting recurrent pneumonia. By six months later, I no longer suffered from hidradenitis. In the ensuing 21 years, I have had a total of exactly 1 kidney stone. I have not had any recurrence of rosacea or hidradenitis (though i still have scars), and I have not had a single episode of bacterial pneumonia (though I’ve had mild viral things, of course). Was it all due to vitamins? Probably not — I changed jobs to one with less stress, moved to a healthier location, etc. But, subjectively, I place a lot of the benefit on the vitamins, and I’m not willing to stop them to check…

There are two variants on vitamin supplementation that do not involve the Pauling hypothesis.

The first is atypical effects of megadoses that likely don’t involve “normal” metabolism (e.g. high dose niacin monotherapy for hyperlipidemia and endothelial effects). But, the cohort issue still comes into play. People react differently to these things. Some folk should respond well (such as me), and some should not. For me, it means a 70-year-old obese ex-smoker has 10% atherosclerotic plaque in his coronaries, and most of that is due to turbulence from an anomalous vessel, not hyperlipidemia. And what does it cost me? Twenty cents a day.

The second are the “body hacking” anti-aging supplements — the senolytics (quercetin, fisetin, etc) and the mitochondrial support supplements (e.g. NMN, methylene blue,etc). That’s a completely different set of literature. The mitochondrial support literature is *kinda* like the Pauling hypothesis in that ageing moves you from an efficiently metabolizing cohort into an inefficiently metabolizing cohort, so the idea is similar. But it’s still a different literature.